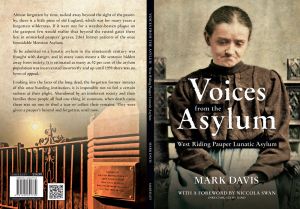

The voices of ‘the apparent insane’ who were admitted to the former pauper lunatic asylum at Menston are for the most preserved in the original medical casebooks catalogued and stored at the West Yorkshire Archive Service in the unique collection identified as C485. Much of the material for the individual patients stories have been sourced from the casebooks, other reference points include contemporary newspapers reports, asylum records and Ancestry online.

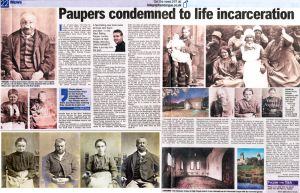

The casebooks contain a wealth of information for both the historical researcher and the genealogist searching out relatives. Many of the terms used in book are distinctly unsavoury by today’s standards and expectations, but it is important that we understand these descriptions and labels are historical and do not reflect modern day treatment and principles. The study of the history of medicine, and more particularly that of psychiatry, often induces in the contemporary reader an understandable sense of relief that he or she is living in the modern world and not in the past. Yet the accounts of the patients in this book, representatives of thousands of people admitted between 1888 (when the asylum opened on 8 October) and 1911 will resonate with all who take an interest in mental health today. Some of the people we meet were paupers who were certified as insane, others became paupers as a result of their mental illness.

Patient confidentiality is protected by the ‘one hundred year rule’ that limits access to records younger than a century to family members. Although data protection and confidentiality protect these former patients from exploitation they do not silence them.

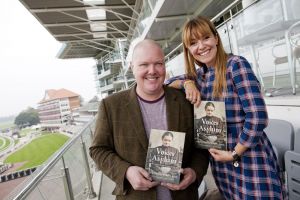

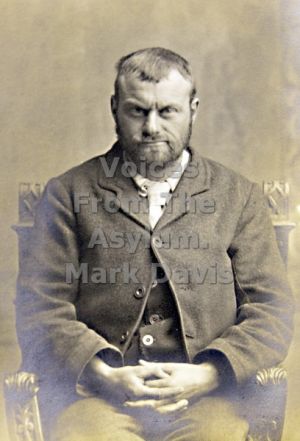

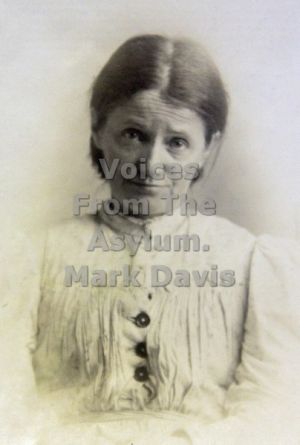

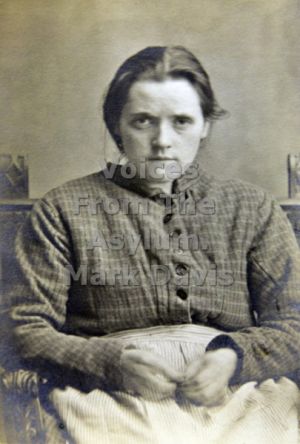

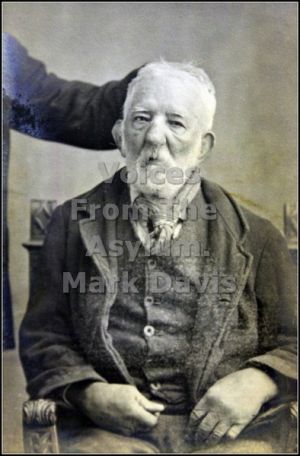

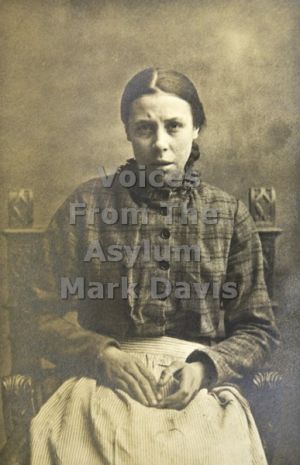

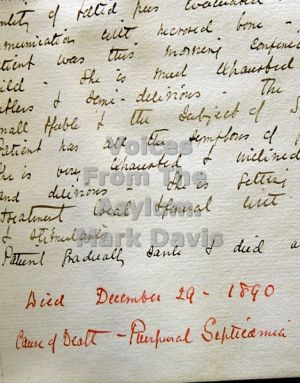

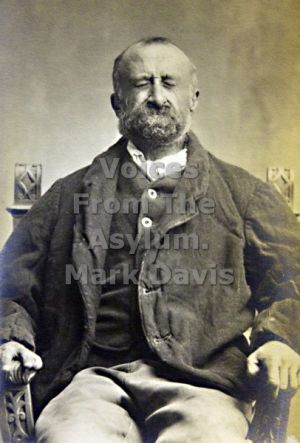

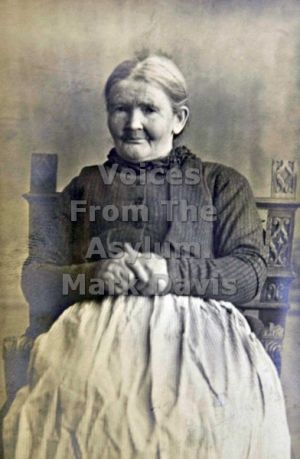

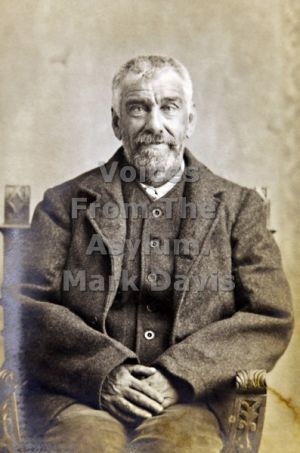

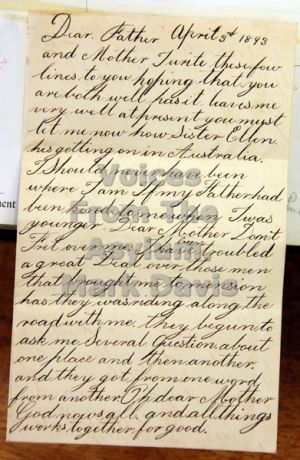

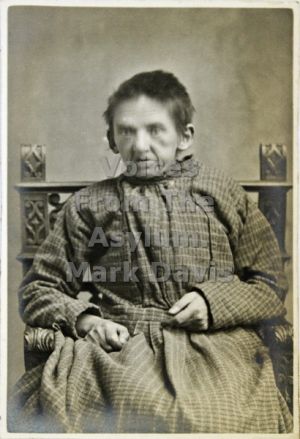

Within this book the patients’ voices are sometimes indirectly heard through the contents of doctors’ certificates and clinical records which have been summarised. More fascinating have been the direct reports of their speech, their letters – as well as those from relatives and friends and of course those thought provoking images, each individual picture gives us a window onto a unique human life. Every personal story in this book reaches out, not only to tell of mental distress, but of life outside the hospital, family, relationships and contemporary attitudes of a Victorian lunatic asylum and culture.

Under the lunacy act of 1845 to which all lunatic asylums were subject, patients had to be certified by two doctors regardless of whether they had any experience in mental illness or not. Once admitted the patient’s physical state, mental condition and previous history were entered into the casebook. Over time progress notes were added at regular intervals as were charts, letters and sometimes pictures. The notes featured in this book were written by the medical staff: the Medical Superintendents, Dr. John Greig McDowall 1888 – November 1906 and Dr. Samuel Edgerley 1906 – December 1933 and the assistant Medical Officers including Dr James.R Whitwell, Dr. Richard Kirwan and Dr.R Clive Walker

The majority of pauper insane patients admitted to Menston were direct transfers from the union workhouse often referred to as the ‘the Bastille’ by the poor in the West Riding. The patients were certified by medical officers in the workhouse infirmary where the selection process took place, others were sent at the direction of the criminal courts having been certified as fit for removal by police doctors. The larger percentage of patients were of the pauper class who were regarded as insane while a smaller percentage had become paupers as a result of their mental illness.

It is unfortunate that the medical records give very little information regarding physical and chemical treatments applied to individual patients. Of course, the fact that treatments are not mentioned does not mean that they were not employed, it may just mean the medical staff thought them not worthy of mention. Medical Superintendent Dr Samuel Edgerley shed some light on the mysterious workings of the hospital in 1929 when discussing treatments with a newspaper reporter investigating claims of cruelty to patients. The Superintendent was quite clear that in his thirty two years of experience at Menston there had not been one single instance of the Strait Jacket being deployed to restrain any patient. He went on to discuss the use of dangerous drugs and stated that only three grams of cocaine had been administered since 1921, Dr Edgerley maintained the principal drugs used were bromide and sleeping draughts, such as Paraldehyde used principally to quieten disruptive patients at night.

The thirty seven patients who relate their stories in this book spent over six hundred and eighty years between them under care and treatment, many lived to a ripe old age spending decades as inpatients, for some life was decidedly shorter. It is a fact that in the early days 98% of patients dying were subject to a post-mortem. The post-mortem was considered an important tool in understanding the cause and effect of mental illness with emphasis on studying brain deformity and scar tissue..

Every patient within this book was laid to rest by the hospital authorities in land set apart on the south side of the hospital estate situated at Buckle Lane. The two acre site complete with a mortuary chapel was drained and laid out in 1890 specifically to bury the unclaimed asylum dead. There are many reasons to justify why families did not collect their relatives remains among them poverty, the stigma of having a relative in the asylum, and sadly, the patient had quite literally been forgotten by family through the sheer passage of time. The cemetery opened on 3 December 1890 at which time Sarah Ann walker aged 45 was laid to rest. When the cemetery eventually closed on the 14th January 1969 upon the funeral of Alice Maud Wardman aged 90 a total of 2860 people had already been interred over the seventy nine years of operational use.

Contrary to various legends, the funeral service in the early days although basic was dignified, the coffin was of plain deal pine and the burial service brief, more often than not only the grave digger and clergy in attendance. Patients were initially interred singularly but in later years buried three deep with only a cast iron marker denoting the grave and row number.

The names of patients whose stories and accounts appear in this book have not been altered or changed . By giving the patients their true names, we rescue their cases from being discussed impassively as no more than examples of Victorian and Edwardian asylum diagnosis and treatment. The stories however do not provide the last word on any of these people, they only represent a snapshot of a time when the individuals were undergoing extreme human distress. As I have been researching and compiling this book I have often wondered how the lives of these patients might have turned out for the better had modern care and treatments been available.

Through this book we can correctly attribute personal lives and experiences, and make their ‘Voices’ count for something, they can educate us all so that we can make sure mistakes of the past are never repeated. The voices of these people deserve to be heard.

Despite being firmly in the 21st century, the fear and the stigma associated with mental illness unfortunately still remains although campaigns like ‘Time to Change’ work tirelessly towards breaking down these barriers.

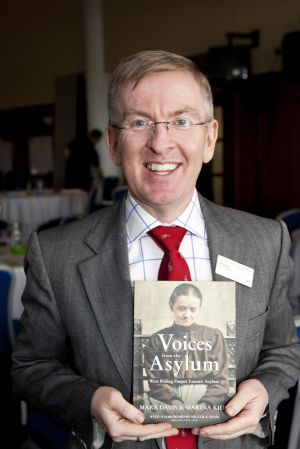

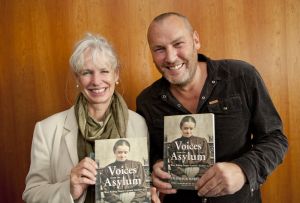

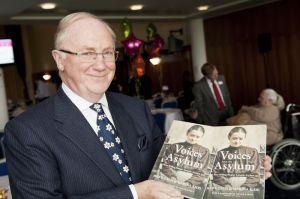

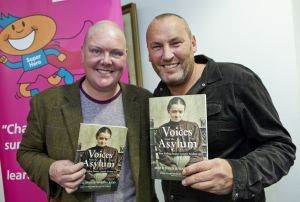

Mark Davis, August 2013

Publication September 24, 2013

Reprint March 2014

One Comment

Thanks for book, great read. Fab insight into the hospital early history. Good work Mark

One Trackback

[…] from the Asylum” by Mark Davis can be found here and a copy of the book was bought at Salt’s Mill in Saltaire, West […]