The Illustrated Weekly Telegraph, Saturday August 30, 1890

THE WIFE MURDER AT BOWLING

Execution of Harrison

“Hangings too Good for Him”

Sharp at the stroke of eight o’clock the black flag was hoisted again over the summit of Armley prison, to denote the execution of James Harrison, for the murder of his wife at Bowling. There were not many spectators around the prison walls, fewer indeed than usually gratify their curiosity by catching a glimpse of the floating black flag. The workmen as they passed to and fro cast a glance at the awe-inspiring black walls and then passed on. The women folk lingered a while and discussed the merits of the case, and they too passed quickly aside. There was no manifest outward interest in the fate of the man. As the hour for the execution rapidly approached, there were a few score who hung about the roadside and in the fields below waiting out of idle curiosity to see the black flag hoisted, as in passing and out of equal curiosity they had seen others before when greater criminals than James Harrison had suffered their last doom in Armley Prison. Billington, the hangman, who has the engagements at Armley, arrived there on Monday afternoon, and was located in the prison, and in consequence of recent instructions from the Home Office and the introduction of a new governor, information is somewhat difficult to obtain. Under such circumstances it is difficult to state the details which occurred, but it is stated that the drop was six feet two. Before this it was hoped there would have been a new “execution chamber” on very much improved principles. It has not yet come into being, and it may be hoped it will not be required. The hangman’s chamber is at present in the old “wheelhouses” where criminals used to tread the wheel and within which Otto Brand, Johnson, well known in Bradford, West, and other murderers have met their just doom. The last execution which took place here was on New Year’s Day of this year, and on the last day of 1889 there was a double execution. Major Lane, the governor of the prison, read to Harrison on Sunday the decision of the home secretary which we published yesterday and with that his last ray of hope vanished.

The culprit received it calmly and collectively as far as outward indications would show, but there was never the less indication that he had hoped that the last dread penalty of the law would not be enforced. His daughters by special permission, again paid him a visit yesterday afternoon, and the parting and grief it is not well to dwell upon. Harrison after seeing his daughters yesterday afternoon was visited by the chaplain of the prison, the Rev Mr Bower, and in the evening became somewhat calmer. He partook of a light supper and retired to rest at 11.45 pm. On retiring to rest the condemned man asked that he should be awakened early, but there was no need for the request, as he himself was aroused by a slight knocking in the neighbourhood of the cell at 5.45. He dressed himself, and doing so quietly observed that he supposed that it was now too late to hope for a reprieve. This was the only observation he made to the warders. The chaplain paid him an early visit, and remained with him in prayer in the condemned cell. The wretched man in the last few hours exhibited more traces of inward consciousness and emotion than he had previously done.

The preparations for the execution were begun shortly before eight, when Billington proceeded to the cell and adjusted some of the straps. The bell from the chapel was tolling, thus announcing the approach of the final moment for the little procession of prison officials, the Under Sheriff and warders from the cell to the scaffold, the chaplain on the way repeating the words of the funeral service. At the lead of the procession walked the governor, Major Lane, and the Under-Sheriff (Mr Edwyn Gray, of York). Then came the chaplain followed by the executioner, and the culprit between two warders, with Chief Warden Taylor in charge of the posse of warders bringing up the rear. With a firm step Harrison walked unassisted to the scaffold, casting at times a furtive glance heavenwards. He never opened his lips on the way to the scaffold; when on it did not respond to the prayers of the chaplain, and died without a passing reference to his awful crime or the dreadful surroundings amid which he met his death. The pause on the scaffold was of the most momentary character, and the six feet two inches drop which Billington gave the condemned man caused instantaneous death with less than the usual amount of muscular twitching observable on such occasions. To those outside the floating of the black flag in a strong breeze and a brief glimpse of sunshine gave the customary indication that the law of the land had once more been vindicated.

The representatives of the press were admitted, along with the jury, to view the body after it had been cut down. The features were then quite natural, and bore no traces of contortion or indications of pain or suffering. Even the rope mark around the neck was not visible, but that was owing to the fact that the condemned man had grown a beard since his confinement. Otherwise his appearance was not altered. He appeared to be in a healthy condition, and had certainly lost no flesh since the morning of the tragedy.

THE INQUEST

After being allowed to hang the usual hour, the body was cut down, and Mr Malcolm, the Leeds Coroner, held an inquiry into the cause of death.

Major Lane, the new Governor of the gaol, said that he found Harrison a prisoner in the gaol when he entered on his duties as Governor of the gaol of the 1st of the month. The man was under sentence of death. He was 36 years of age, and was condemned to death for the murder of his wife Hannah Harrison, at Bradford. This morning he handed over the man to the Under-Sheriff for execution, and was present when the sentence of the law was carried out.

Mr Gray, Under-Sheriff said that he was present at the Assizes when Harrison was sentenced to death, and also this morning when the sentence was carried into effect.

Dr Edwards, surgeon at Armley Gaol, said he was also present at the execution. Death was brought about by strangulation by hanging, and was instantaneous. The immediate cause of death was dislocation of the spine.

The jury returned a verdict in accordance with the evidence given.

FAREWELL INTERVIEWS WITH RELATIVES

HIS CONDUCT IN PRISON

Harrison had a final interview with his friends in Armley prison on Saturday. Since his incarceration in the condemned cell the culprit has given very little trouble to the warders. He has preserved a calm and patient demeanour, has eaten and slept well, and his conduct has been very unlike that of many of the men given in charge of the officers of the prison to suffer at the appointed time the last dread penalty of the law. The day following his condemnation Harrison was seized with a rather bad attack of diarrhoea, and again on Saturday he suffered from the same complaint, but otherwise he enjoyed good health, and was in remarkably good spirits for a man awaiting his sorrowful fate at the hangman’s hands. One of his nearest relatives had an interview with him a few days after his trial, and he then inquired

IF ANYTHING WAS BEING DONE

By means of a petition to give effect to the recommendation of the jury to the mercy on the ground of the provocation he had he said received from his wife. He was then informed that a petition was in course of preparation. At this he seemed to brighten up. He also

INQUIRED AFTER HIS CHILDREN

Sad said he hoped they would grow up to be good children and that some kind friends would help to look after them. He was told that they were as happy as could be expected, and hoped to be able to soon come and see their father.

THE PETITION

To which Harrison referred wad duly circulated in Bowling, but the signatures were not sufficiently numerous to justify those who promoted it sending it forward to the Home Secretary. Besides this there were other circumstances which rendered it very doubtful that the prayer of the memorialists would be sufficiently weighty to advise the Queen to extend her merciful prerogative to the condemned man, and as a consequence no public effort was made to set aside the sentence of the law. Mr J J Wright, who conducted Harrison’s case when it was before the magistrates, wrote to the Home Secretary calling attention to the recommendation of the jury to mercy, but only to elicit the reply that the Home Secretary could not see his way to adopt the recommendation.

After the first visit paid to the prison Harrison improved in both health and spirits, and although he maintained a somewhat solid demeanour he was not averse to conversation with his guardians the prison warders, who rendered the brief span of life he was left to enjoy as cheerful as the gloomy surroundings should permit.

HE TALKED ABOUT THE MURDER,

And reiterated the statement as to the alleged provocation he received. Once or twice his little children wrote to him kindly childlike letters breathing a spirit of deep affection, and lamenting the awful position in which their parent was placed. To these no answer was received, and this is probably attributable to the fact of Harrison not being much of a scholar, and evinced no inclination to commit his thoughts to paper. During the whole time since his condemnation Harrison has been

GUARDED NIGHT AND DAY

By two warders and to help him to ease his mind they frequently read to him books from the prison library. In the matter of diet he enjoyed the usual liberty extended to men sentenced to death. He could not have any stimulants, but in the matter of food was supplied with nearly anything he could fancy. Mutton chops, ham and eggs, beefsteaks and roast meat were supplied him, and he seemed to relish his meals. During the last few days somewhat of a change came over him. He seemed to pay deeper attention to the ministrations of the prison chaplain, and as no communication of any chance was received of a reprieve he gradually came to the conclusion that he would have to suffer death at the hangman’s hands, and as seriously prepared himself for his fate. One little relaxation of the rules permissible under such painful circumstances was the granting of the governor of a pipe and tobacco to Harrison. Of this he availed himself to a considerable extent, and smoked no fewer than 14 to 16 ounces of thick twist, and coloured one or two clay pipes which he wished to have sent to some friends as a keepsake.

THE FINAL LEAVE-TAKINGS

Were on Saturday, and Harrison had his last look and conversations with those who were nearest to him. They took place during the afternoon, and were naturally of a painful character. The first person who visited him were two cousins, one of whom mentioned some matters which, not being permissible according to the rules, was stopped by the chief warder. Both of these ladies urged Harrison to prepare for death, and he seemed to pay heed to their request. With them, however, he was not particularly free in his conversation, but was more communicative to some other friends, who brought with them the three little daughters of Harrison. The surroundings of the visiting cell are not at any time of the most pleasant kind. The prisoner has to stand behind a massive row of iron bars and his visitors stand some three or four feet away, with the warders seated between them. Conversation has to be carried out in a loud tone of voice, and the warders are bound to hear every word that is said. To his later visitors Harrison said that the police evidence as to his coming down the stairs and stepping over the body of his prostrate wife when the constables entered was utterly false. He told his auditors that when in his passion he struck his wife with the poker, he never had the knife in his hand, and that when he realised what he had done, he sat down in the chair and awaited the arrival of the police. He also repeated his complaint as to the provocation he had received from his wife, but said he was truly sorry for what he had done, and hoped for forgiveness for his deed. In sobbing tones he told his friends he was now fully prepared to die, and

ONLY HOPED FOR A REPRIEVE FOR THE SAKE OF THE CHILDREN

He hoped, however, they would grow up good children; that they would not forget their father and mother, and would grow up to be good children to those who might bring them up. Harrison faltered in his voice towards the end of the time allotted for the interview. As it closed father and children embraced in a touching and affectionate manner, and amid an affecting scene the last goodbye was uttered and the last kiss imprinted upon the cheeks of the children, who sobbed painfully as they quitted the cell.

HARRISON’S FAREWELL TO HIS CHILDREN

In a farewell, and in fact the only letter James Harrison has caused to be indited, he bids an affectionate and warm farewell to his children. The letter was written late on Monday night by a warder, at the dictation of Harrison, and in it he requests the children to be of good cheer, and to behave themselves with whom they come in contact, and expresses the hope that they will all meet again in heaven.

It is somewhat curious that the condemned man since his incarceration in Armley prison never once asked or inquired for Mrs Bella Duckworth, his foster mother, although they were said to have an affectionate regard for each other.

An explanation for the great firmness exhibited by Harrison on Tuesday may be found in the question put to him on Saturday by a relative – “Do you think you’ll duff?” “Nay,” replied Harrison, “I shan’t duff if I were to be hanged twice over.”

THE STORY OF THE CRIME

Rather more than three months ago James Harrison, a dyer’s labourer, murdered his wife by striking her on the head with a poker, at the house that they resided in at 7 Lord Street, Bowling. It was soon after the break of the day on May 12th last that Harrison dragged his wife out of bed and first attacked her with a knife and then smashed in her skull with a heavy kitchen poker. Today he has expiated his guilt on the scaffold at the hands of the hangman in Armley Gaol.

The story of the crime is a sad one, there resided in the house Harrison and his wife, three children, and an old woman, Bella Duckworth, who had acted as foster mother to Harrison. The murderer had been out of work for six or seven weeks, and was to have started again that morning at Messrs Ripley’s, where he was formerly employed. All the occupants of the cottage slept in one upstairs room. During the night everything was perfectly peaceful, and the old woman got up about five o’clock, and went downstairs to light the fire and get breakfast ready for Harrison and his wife and the children before they went off to the mill…soon after Harrison came down. Mrs Duckworth saw him pick up something and partly conceal it, and inquired “What has he there?” He replied, “I have this,” showing a carving knife.

“I’M GOING TO DO IT THIS MORNING”

The old woman thought that the threat was a bit of nonsense, but she was speedily undeceived in a horrible manner, Harrison ran upstairs, an act which was followed by loud screams from the bedroom, and frightened by the screams the old woman ran out of the house. He seized his wife by the hair of the head, and attempted to attack her with the knife, but the woman wrenched it away from him. The culprit however, again got possession of the knife and struck his defenceless wife in the side with it, the children at the same time wildly screaming for help. As he pulled the knife from her hands the poor woman in piteous tones exclaimed, “”Oh spare me for the sake of the bairns. Spare my life and you need not go to this job; I’ll work for you.” The appeal for mercy was either unheard or unheeded amid the terrified screams of the children. Harrison dragged his wife across the floor of the bedroom, down a short flight of stairs and there seizing a poker relentlessly beat his wife about the head with this murderous weapon until he had destroyed her life. The neighbours stated at the time that the

THUMPING WAS SOMETHING AWFUL

And the medical testimony produced at the inquest and at the trial showed that though the head of the unfortunate woman was battered in by repeated blows yet one of the early blows must have caused insensibility, and would have spared the pain of the attack made upon her. There were only child witnesses in the house at the time of the murder, and they did not stay to see the terrible work completed. Mrs Duckworth fled precipitately at the sight of the knife, but Matilda stayed somewhat longer. This is the lucid statement she made to a “Telegraph” reporter on the morning of the murder. She said: I was awoke by hearing mother and father quarrelling. I can’t tell you how it began or who began it. I and my sisters and grandmother slept in the same room as my father and mother. Grandmother slept with us. I heard mother say to father “”What have I done wrong to you?” my father never spoke. My grandmother said “What are you going to do Jim?” and father then said “Oh yes, but I am, “She asked what he had got in his hand, and he then showed her the knife. Mother was in bed at the time. She was not dressed. Father tried to hit her with the knife. It was an ordinary table knife, and I know it was not very sharp. He then caught hold of her, and dragged her out of bed, and tried to hit her with the knife. They struggled on the staircase, and mother got the knife out of his hand. He cut mother’s hand when she pulled the knife out of his hand. They then had a terrible struggle on the staircase. Father got hold of one end of the knife and mother the other. Father pulled mother downstairs by the hair, and as he could not get the knife again he ran and got the poker. He got hold of her hair and then hit her with the poker. I saw him hit her once, and then I ran out in the street and I have not seen my mother since. When he was dragging my mother down the stairs I heard her saying to him “Spare me, oh spare my life.” She said that several times. I heard mother say “If you don’t want to go to work you needn’t. You can take a month if you will only spare my life.” She said that several times. I heard mother say “You can take a month if you will only spare my life.” My father did not then say anything. When my grandmother saw he had a knife she told me to throw up the window, and I did so. I shouted murder, but no one came. There were a lot of men passing the street bottom at the time, but they did not come. When I saw my father had a knife I said, “Oh, don’t father,” and he said, “You keep away, love, I won’t hurt you,” and he then pushed us away. Me and my sisters tried to drag him away, but we couldn’t. I was last to go out of the house. I did not see my father hit mother with the poker more than once, but we heard him hitting her after he shut the door.

A BLOODSTAINEED KNIFE AND POKER

Found in the kitchen, hear out the children’s version of the crime, and the latter part is also corroborated by the neighbours, who say that the “thumping was something awful.” The murderer was not long about his work, for, when the first neighbour entered the house, about half past five, the woman was to all appearance stone dead, and the room showed little signs of a struggle. The body of the woman lay huddled in a heap at the foot of the staircase, chairs and table and wall being splashed with blood. The murderer after finishing his work went upstairs into the bedroom and is said to have

CYNICALLY SMILED AT THE HORRIFIED CROWD

Who had assembled outside the house when the three children rushing out in their nightdresses and alarmed the street by their lamentations? P.C. Foster arrived just after the murder, and Dr. Butler, who lives near, was summoned at once, but, could do nothing more than declare the woman dead. Harrison was taken into custody by Foster, and judging by his conduct was altogether callous or unable to realise his position. He was quite nonchalant, and

LAUGHED AND BID GOOD MORNING

To his acquaintances as he was being taken away in custody. For this inhuman conduct the temporary exhilaration well known by medical men to follow callous natures on such a crime was doubtless responsible. After his arrest the prisoner was removed and taken to the Bowling Police Station and subsequently to the Town Hall, where he was charged with the murder of his wife and remanded for a week. On the Friday following the commission of the deed Mr Coroner Hutchinson and a jury held an inquest, and after hearing evidence bearing out the above facts he was committed to take his trial at the last Assizes on a charge of wilful murder, a verdict the jury found after two minutes’ consultation. The magistrates also at the magisterial investigation the following day committed him upon a similar charge, upon, which he was tried by Mr Justice Charles and a jury at the Assizes on August 12th. Mr Mellor, who defended the prisoner at the Judge’s request, could only raise the plea that the prisoner had received provocation from his wife, but there was little or no evidence to support it, and the recommendation of the jury to mercy which the plea secured did not prove sufficient to save Harrison from the hangman’s hands.

THE MURDERED WOMAN AND HER HUSBAND

Were well known in the neighbourhood where they lived. He was the adopted son of the old woman Bella Duckworth. He was 38 years old, and lived in or near Lord Street ever since he was a fortnight old. His ill treatment of his wife has been notorious, but no one eared to interfere in their domestic affairs. Harrison being a very powerful man, and, as a neighbour put it, “ready with a bat for anyone.” He had worked at Bowling Dye works, but about two months before the murder was stopped by the foreman for breaking time and drinking. After that he did nothing but loaf about and drink when he had the chance. On the morning of the murder he was to have gone to work, and the idea, according to the neighbours, was very distasteful to him. Some of his friends occupy a very respectable position of life in Bradford, and of Harrison it has been said by some who knew him that when keeping away from drink there was no better husband about, but absences from the public house was not a marked characteristic in Harrisons daily life, and when in drink his temper was uncontrollable. A brother of his was of the same disposition as the prisoner. He too was very fond of drink, did little or no work, and at last found an asylum in the county building at Menston, where he soon died a raving lunatic. For seven weeks before the murder Harrison did no work at Messrs Ripley’s, and during that time he was chiefly fed by his relatives, while his wife by going to the mill struggled to keep a roof over the heads of herself and children.

DRINK IS UNDOUBTEDLY THE EVIL

Which led to the commission of the brutal murder, for his nearest friends stated at the time of the murder that when in work Harrison always used to give his wife his full wages to the last halfpenny, keeping only for spending any little overtime he had made. He would readily assist in preparing the Sunday dinner, and do any little odd jobs about the house to assist his wife in her household duties. He was also given the character of being an affectionate father towards his children, who when he was in drink could often better manage him than the murdered woman. Of his foster mother, Mrs Duckworth, he was also very fond, and it was in her house the prisoner and his wife resided after their marriage.

There is little doubt, however, that on the whole their married life was not a happy one. On the Sunday before the murder there had been some unpleasantness during the dinner hour about a piece of meat which had been sent by a relative for the Sunday dinner. Words arose between them at the dinner table, and the prisoner remarked to his wife: “If you ever touch that meat I hope it will rot in your belly,” and also added an observation that if she used the gravy it would scald her. The consequences of this language was that Mrs Harrison did not eat any of the meat. The murdered woman was undoubtedly a clean, steady, industrious woman, and used to work at Dudley Hill in one of the mills to help to keep the house together. She had no relatives in Bradford, but it was understood her mother lived in the neighbourhood of Manchester. She had eight children by Harrison, but only three of them survive, and upon them the mother devoted her spare time. Her neighbours all had a kindly word to say on her behalf both as a mother and wife.

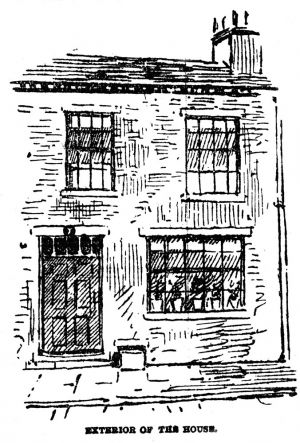

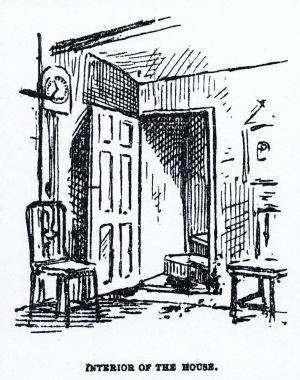

SCENE OF THE CRIME

Lord Street consists of two rows of cottages of the type of the one represented. No. 7 is about the middle house on the side nearest the centre of the town. The only features of difference between this and most other streets of cottage property is that the usual passages leading at intervals to the back row are absent. The house consists of one good sized room on the ground floor-joint kitchen and sitting room, with the usual bed chamber above, access to the latter being gained by a staircase running across the back of the apartment. The doorway leading to the staircase, and the spot where the murderer dragged his victim to finish the crime, are shown very faithfully in the interior sketch.

One portrait of the murderer and his victim were taken from a photograph taken eleven years ago, not very long after their marriage. Notwithstanding the lapse of time, this photograph, which is the only one in existence, is regarded by those who knew the parties to be a good one, especially as regards Harrison.

FUNERAL OF THE VICTIM

Another incident connected with the Bradford murder took place, when the wife and victim of the man James Harrison was interred at the Bowling Cemetery. Mrs Harrison was evidently highly self-esteemed and respected by those with whom she was acquainted, and a large number of people desired to be allowed to take a last glimpse of the body as it laid in the coffin at No 7 Lord Street. So many, in attendance were there that a great proportion of the applicants had to be refused, and only the close intimate friends were admitted to the house for purpose of seeing the deceased woman. Those who were granted the privilege, however, were gratified to find that the features of the murdered woman were of a perfectly natural expression, and that only very small marks on the face were noticeable.

The funeral left the house for the cemetery about 2.30, but for a short time before two o’clock Lord Street, which is open at one end, was crowded with people, women for the most part, who seemed not to care for the heavy rain falling at the time. About the same time the clouds cleared and the sun began to shine. This had the effect of bringing numerous others to the spectacle and by 2.30 Wakefield Road was crowded for some distance with persons wishing to see the funeral procession. During the period of waiting the dastardly outrage was the general topic of conversation, and the remarks were damnatory of the life pursued by Harrison and his criminal deed of Monday morning were not stinted. Nobody seemed to have a good word of any sort to say for the murderer. “He never was any good” appeared be the petty unanimously agreed upon verdict, a hanging according to the popular judgement seems “too good for him.” “But,” added one, “if they don’t hang him they be owt to hang them, cause he was no lunatic when he told the youngsters to get out of the way of Mrs Harrison, it is said, “she was far too good for him, and a few would have put up with as much as she had.” Soon after two o’clock Sub-Inspector Barraclough, accompanied by six policemen, arrive on the scene, and with some little difficulty succeeded in clearing Lord Street. Then the Rev J. Hammer arrived and went to the house. Mr Hammer Is vicar of St John’s, Bowling, where the children of the deceased woman attended, and he came to say a few words of prayer at the house before the body was taken away to the cemetery. A few minutes after the appointed time the coffin containing the body was carted down the street and placed on the hearse as it stood in Wakefield Road, and the funeral procession started via Bowling Hall Road and Parkside on its way to the cemetery. There were only a few carriages, and they were occupied by members of the family and relations. Amongst these were Mrs Duckworth, whose adopted son Harrison was; the daughters of the deceased Matilda, Alice Ann and Sophia; Mrs Clayton, Harrisons sister, and Mr John Harrison and Mr Arthur Harrison, his brothers; Mrs Pinder, Mrs Dawson, Mr Johnson and Miss Hairet, and other relations. After they followed on foot, a number of friends, and a body of the weavers from the place where the deceased had been employed. Eventually the cemetery was reached, and the funeral service having been read as the body was committed to the grave.

The coffin was a black one, and the plate bore the inscription “Anne Harrison, died 12th May, 1890, aged 38 years.” It was covered with floral tokens of respect from relations, friends and the weavers present at the funeral.

The Prisoner’s Demeanour Before his Committal

When apprehended, charged before the magistrates, and before the Judge at the Assizes, the prisoner maintained a careless attitude. His attitude at the Coroner’s Court is fairly indicative of his general demeanour. His tone of putting questions was in many respects cynical, and even contemptuous. He did not appear in the least affected when his own children gave evidence against him. One incident illustrative of his conduct in court was when asked to question his foster mother. He sprang from the chair to his feet from where he had been seated. This somewhat alarmed the old lady, who was very nervous, and she shrank from him. “Oh,” exclaimed the prisoner jauntily, “you need not be frightened.” The implements of his cruelty-the poker and the knife-the sight of what evidently caused the old lady great pain, he only eyed as objects of curiosity. The Chief Constable, thinking to render the prisoner a kindness, went and warned him not to make too many statements, as they might be used in evidence against him. Harrison, however, did not regard the act as anything particularly beneficial to himself, and merely replied “Oh, that’s right enough,’ and as the Chief retired he cast a side glance upon him which was indicative rather of suspicion than gratitude. He smiled contemptuously whilst the doctor described the dreadful wounds, and he did the same after the Coroner had advised the jury to return a verdict of the capital offence against him.

At the trial at Assizes, Harrison at the outset paid little or no heed to what was taking place, and which so immediately concerned his fate. At the commencement of the trial he stared at the Judge and Jury in a very indifferent fashion, but as the case proceeded, and Mr Mellor addressed the Jury on his behalf his interest became more lame, though at no point was it very great. When the reference was made by counsel to the attention he had paid to his children was the only time when his better nature exhibited itself. On hearing the sentence of death the culprit simply stared at the jury and walked out of the dock in the calmest possible fashion.

We understand that one of the reasons why the petition for a reprieve was not persevered with was that the Judge in an interview with Mr Mellor (who defended the prisoner at the Assizes) subsequent to the trial intimated that he saw no reason to give effect to the recommendation of the jury.