“There they stand, isolated, majestic, imperious, brooded over by the gigantic water-tower and chimney combined, rising unmistakable and daunting out of the countryside – the asylums which our forefathers built with such immense solidity to express the notions of their day. Do not for a moment underestimate their powers of resistance to our assault”– As said by the then Government Health Minister Enoch Powell in March 1961 when he made the first steps to make these once self-contained villages for the insane a thing of the past.

Once a familiar landmark of the British landscape, the old Victorian asylum were places where legends were created. They were places of mystery where according to folk, ‘all sorts went on’. Even school children in the playground would taunt each other with, ‘You’re mental! You’re off to Menston’, relating to High Royds Psychiatric Hospital. Such phrases as ‘going round the bend’ originate from the fact that many an asylum could be found at the top of an impressive curved drive, effectively hiding the institution from the prying eye of the inquisitive public.

In the nineteenth century, reception in to the asylum was potentially the beginning of an arbitrary life sentence in one of many large, seventy bed dormitories. To some it was worse than going to prison; at least with the prison you had a release date whereas at the asylum there was only a 30 to 50 per cent discharge rate. As a rule the asylum would be located in relative isolation within reasonable distance from the local town and railway. During the latter part of the nineteenth century county asylums were built at a rapid rate to cater for society’s intolerance to behaviour and the increasing number of human wreckage associated with the newly industrialised society. The patient population was drawn primarily from the despised pauper class, although limited numbers of private paying patients were admitted. The majority of paupers were direct transfers from the workhouse union (referred to in Bradford by the poor as the ‘Bastille’) and the Magistrates court upon the recommendation of the police doctor. The patients, or inmates as they were referred to, came from all walks of life, although the biggest percentage were of the unskilled class such as labourers or mill workers. However, it was not unheard of for a policeman or even a schoolmaster to be admitted under the banner of care and treatment. When researching the nineteenth-century patient it soon becomes clear that the noted probable cause of insanity and how that cause manifests itself can appear worlds apart. For example in the case one patient a young woman of twenty-eight, the supposed cause was ‘conflict with husband’, in reality she had GPI (general paralysis of the insane), the conflict being her husband had infected her with syphilis. Inmates with GPI accounted for a good proportion of the asylum population as did the manic, the depressed and the intemperate. For example in the case one patient a young woman of twenty-eight, the supposed cause was ‘conflict with husband’, in reality she had GPI (general paralysis of the insane), the conflict being her husband had infected her with syphilis. Inmates with GPI accounted for a good proportion of the asylum population as did the manic, the depressed and the intemperate.

Treatment for the Victorian patient ranged from opium as the main sedative in the mid-nineteenth century to laudanum, bromide, and chloral hydrate whilst physical treatment included Turkish or hot baths, wet sheet packs and electric stimulation. Staff were invariably employed from the local population. Thus in time small local towns grew with generations of families being employed. Experience in those early days was not required: quite simply if you were physically fit and either a good sportsman or able to play a musical instrument then you were very likely to be offered a position on the staff.

Times have certainly moved on, the stigma of mental health is a mere shadow of itself in 2014 compared to Victorian intolerance, where families would disown a relative for fear of themselves being labelled insane. Many believed insanity was hereditary.

It is very easy to demonise these institutions but in order to get a better understanding one needs to remove the age-old preconceptions. Certainly it’s true that for some people life in the asylum represented a living hell, but for others there came an acceptance and tolerance and with that a quality of life. It is wise to remember that no one is immune from mental illness. It can happen in one form or another to anyone at anytime.

Through this book which features seventeen former asylums- mental hospitals we take a look at this hidden world and visit the corridors and dormitories where thousands of people lived out their lives under care treatment. The pictures take us to a world far removed from our own where we can justifiably breath a sigh of relief and be thankful that the days of possibility of incarceration in a lunatic asylum are over…

Publication 19 July 2014

A new book of photographs published by Amberley explores the obscure and almost forgotten world of Britain’s pauper lunatic asylums, ‘self contained villages for the apparently insane’.

HAUNTING PHOTOGRAPHS OF BRITAIN’S VICTORIAN PAUPER LUNATIC ASYLUMS

http://www.designcurial.com/news/haunting-photographs-of-britains-victorian-pauper-lunatic-asylums1-4334980/

A new book, published by Amberley and written by Mark Davis, explores the fascinating history of Britain’s Pauper Lunatic Asylums, huge, isolated buildings designed to keep those labelled ‘mad’ and ‘insane’ out of sight and mind of the rest of Victorian society.

According to Davis, ‘In the 19th century, reception into the asylum was potentially the beginning of an arbitrary life sentence in one of many large, seventy-bed dormitories. To some it was worse than going to prison; at least with a prison you had a release date.’

In fact only 30-50- per cent of people committed to the pauper lunatic asylums were ever discharged.

According to the book, ‘During the latter part of the 19th century, county asylums were built at a rapid rate to cater for society’s intolerance to behaviour and the increasing human wreckage associated with the newly industrialised society.’

Most of the patients were poor.

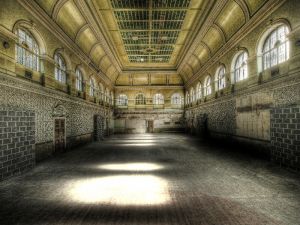

However, like many Victorian municipal buildings, most of the asylums were carefully designed and built. Now, most are derelict, crumbling remnants of what they used to be; but through their decay it is still possible to gimps the strange and sometimes terrifying history of these houses for the insane.

Here are some of our favourite images from the book.

One of the galleries at Staffordshire County Asylum

An abandoned wheelchair at North Wales County Pauper Lunatic Asylum

At Eglington Pauper Lunatic Asylum: stairs are enclosed to prevent suicides

The assent to the east tower at Eglington Pauper Lunatic Asylum

The remains of a telephone box at Linconshire County Lunatic Asylum

A ward at North Wales County Pauper Lunatic Asylum

Scriblings in the clocktower of Lanark District Pauper Lunatic Asylum